From issue 1.1 Jan-Feb 2022 of Girls to the Front!

An interview with Barbara Black, author of Music From a Strange Planet

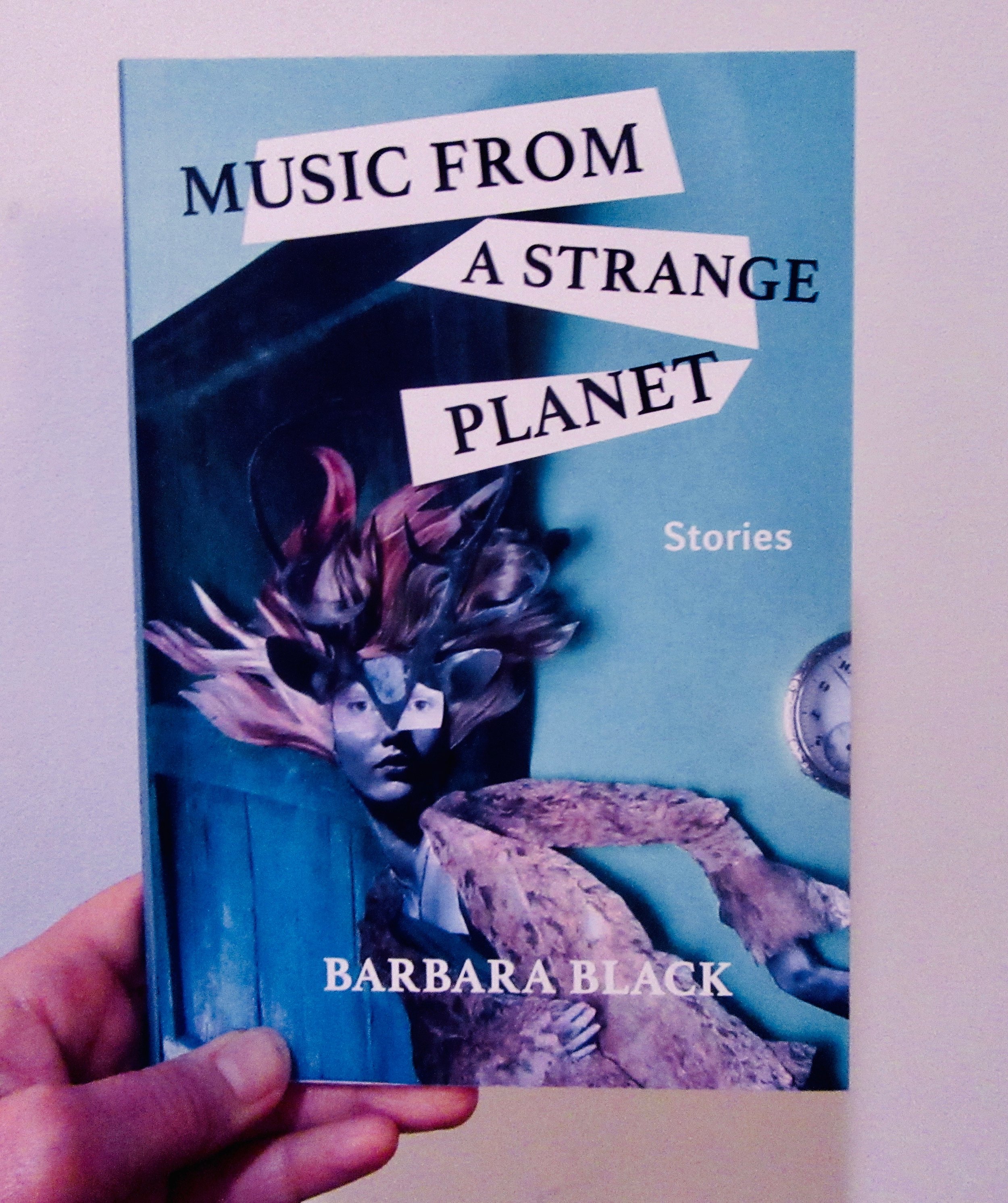

Barbara Black’s debut collection of short-short stories, Music From a Strange Planet, came out with Caitlin Press in Spring 2021. Her book has already made the 49th Shelf Books of the Year 2021 list and I’m sure there will be more accolades to come! I absolutely loved this book and am so glad Barbara agreed to answer a few questions about it for me.

Insects play a prominent role in your book. Can you tell me about where this comes from?

I was a dreamy, sometimes solitary child (but not an only child) and, in addition to loving animals, I liked to observe things and to inhabit small worlds. Hence, insects. My sister and I raised beetles in the basement. I spent hours in the yard watching ants, moths, beetles, worms go about their small-world tasks. I never collected or killed them. My garden-loving Nana used to tell a story that, when she was viciously stomping on snails, the five-year-old me said, “Don’t do that. They have every right to live like we do.” Perhaps I was a natural Buddhist. My original title for Music from a Strange Planet was The Lives of Insects which at some point I deemed too narrow and peculiar. However, I was still interested in writing stories that explored the interconnectivity of nature/insects/animals with humans. Now that I’m older, I’m interested in native pollinators in my own garden and region and how to restore ecosystems so we can sustain the local flora and fauna for years to come. Just one other point. Yes, I did like the Lilliputian world of diminutive creatures, and what accompanied this was a fascination with the subterranean structure of things and a heightened ability to detect subtext. This is one of the reasons I adore the short story genre, both writing and reading it.

You must have done a lot of research in order to write about all of the different settings/scenarios/professions you wrote about in this book. How did you go about doing all of it/how long did it take, etc.?

Research is a time-consuming activity that I happen to love. And it’s also susceptible to happenstance, which I also love. Many times, as I was researching a detail for one of the stories, something new would turn up that was a perfect addition to the story. For example, when I was researching landscape features for my Scottish story “The Mist-Covered Mountains,” I ran across several articles about wind turbines in the Highlands, often erected by the landowners. I added that to the story to give it a more contemporary setting and to illustrate a dilemma for the main character who was lonely and considering selling his property. And searching for information on cicadas, I stumbled upon CicadaMania, which sounds just like something I would make up, but was an actual website devoted to all things cicada, including news on upcoming brood emergences, audio recordings of cicada songs, and the decibel levels of the loudest varieties. From there I bounced around and discovered that there is both a dedicated group of people who travel to witness cicada emergence events and that you could buy T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Sing Fly Mate Die,” hence my story title. I also read books about human interrelations with various creatures in nature, several articles about the North American porcupine and northern caribou, learned about “furries” and had a chat with a Japan ex-pat who enlightened me about cultural habits in that country. Less than 5% of what you research makes it in to the final story. But actually, research is another stage in the story-making process that takes you out of the micro-world of your story and lets you see it in a greater context.

What draws you to the form of microfiction? What do you like about it and/or not like about writing longer works? Also: do you have any inspiring books of microfiction to recommend?

Technically, my short stories are too long to be microfictions, which usually cut off at 1000 words. But several are also unusually short for a short story. (Compression is my forté.) So maybe I inadvertently invented an in-between genre—short-short stories? Books in this word-count category are rarer, but a couple that come to mind are You’re An Animal, Viskovitz! by Alessandro Boffa, an abundantly quirky and cheeky creation of “ironic fables” that run the gamut from a Buddhist police dog to a microbe with an inferiority complex. And Etgar Keret’s The Girl on the Fridge, a contemporary and coolly toned collection that delivers strange, astonishing tales in a very brief space.

I’m a minimalist when it comes to writing. I like compression and conciseness, intentional but not intrusive use of language. It’s the same when I write poetry. So, short story writing as well as micro and flash fiction are my preferred genres. I love packing stories with subtext so my best readers can detect what’s going on both on and under the surface. I operate on a sentence-level with my writing. I mostly find novels long-winded and wordy, but there are the occasional special novels that get me hooked.

Take me through the process of writing one of your stories. It seems something sparks your interest (say a story about wind farms on the Shetland islands) and then how do you go about building a story around it?

I would have to say that I am a writer with an, uh, organic approach to writing. No rituals, prescriptive procedures or word-count sessions for me. No “mapping out” the story with arcs and other unnecessary architecture. I work randomly (it seems, but it is a sort of method that I know and trust) and intuitively. I court the subconscious and stalk the perfect opening line to get the story off to a crackling start. You might say that my approach is writing from the inside out, as George Saunders would put it. That the structure, tone, and trajectory arises from the story itself, is not determined beforehand. Essentially, I mostly begin with a character whose being and situation will influence all aspects of the story. I never write down any description of the character. I hold this character (and attendant idea) in my head for an incubating period, to see what the character might say or do. The story starts the moment I hear a line—whether it’s in first or third person—that kick starts everything. It feels to me like a kind of theatrical process, in the sense that I don’t write my way in. I assume the character as an actor might do. This is how the first draft arises. After that is complete, I may actually start to employ more literary devices to shape the story. And then drafts and drafts and more drafts as my relationship to and understanding of the character and plot deepens.

Thanks so much for your time and for your book, Barbara!

Thank you for the interview, Susan. It’s been a pleasure!